Black Monday (1987)

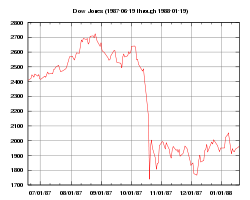

In finance, Black Monday refers to Monday, 19 October, 1987, when stock markets around the world crashed, shedding a huge value in a very short time. The crash began in Hong Kong, spread west through international time zones to Europe, hitting the United States after other markets had already declined by a significant margin. The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) dropped by 508 points to 1738.74 (22.61%).[1]

Contents |

Losses

By the end of October, stock markets in Hong Kong had fallen 45.5%, Australia 41.8%, Spain 31%, the United Kingdom 26.4%, the United States 22.68%, and Canada 22.5%. New Zealand's market was hit especially hard, falling about 60% from its 1987 peak, and taking several years to recover.[2] (The terms Black Monday and Black Tuesday are also applied to October 28 and 29, 1929, which occurred after Black Thursday on October 24, which started the Stock Market Crash of 1929. In Australia and New Zealand the 1987 crash is also referred to as Black Tuesday because of the timezone difference.)

The Black Monday decline was the largest one-day percentage decline in stock market history. Other large declines have occurred after periods of market closure, such as, in the USA, on Monday, September 17, 2001, the first day that the US market was open following the September 11, 2001 attacks. (Saturday, December 12, 1914, is sometimes erroneously cited[3][4] as the largest one-day percentage decline of the DJIA. In reality, the ostensible decline of 24.39% was created retroactively by a redefinition of the DJIA in 1916.[5][6])

Interestingly, the DJIA was positive for the 1987 calendar year. It opened on January 2, 1987, at 1,897 points and would close on December 31, 1987, at 1,939 points. The DJIA did not regain its August 25, 1987 closing high of 2,722 points until almost two years later.

Mysteriousness

A degree of mystery is associated with the 1987 crash.

Important assumptions concerning human rationality, the efficient-market hypothesis, and economic equilibrium were brought into question by the event. Debate as to the cause of the crash still continues many years after the event, with no firm conclusions reached.

In the wake of the crash, markets around the world were put on restricted trading primarily because sorting out the orders that had come in was beyond the computer technology of the time. This also gave the Federal Reserve and other central banks time to pump liquidity into the system to prevent a further downdraft. While pessimism reigned, the DJIA bottomed on October 20.

Following the stock market crash, a group of 33 eminent economists from various nations met in Washington, D.C. in December 1987, and collectively predicted that “the next few years could be the most troubled since the 1930s”.[7] In fact, calendar year 1987 had an overall gain, as did 1988 and 1989.

Timeline

In 1986, the United States economy began shifting from a rapidly growing recovery to a slower growing expansion, which resulted in a "soft landing" as the economy slowed and inflation dropped. The stock market advanced significantly, with the Dow peaking in August 1987 at 2722 points, or 44% over the previous year's closing of 1895 points.

On October 14, the DJIA dropped 95.46 points (a then record) to 2412.70, and fell another 58 points the next day, down over 12% from the August 25 all-time high. On Friday, October 16, when all the markets in London were unexpectedly closed due to the Great Storm of 1987, the DJIA closed down another 108.35 points to close at 2246.74 on record volume. Treasury Secretary James Baker stated concerns about the falling prices. That weekend many investors worried over their stock investments.

The crash began in Far Eastern markets the morning of October 19. Later that morning, two U.S. warships shelled an Iranian oil platform in the Persian Gulf in response to Iran's Silkworm missile attack on the U.S. flagged ship MV Sea Isle City.[8]

In the UK, future British prime minister Tony Blair appeared on the BBC to speak about the crash as the City spokesperson for the opposition Labour party[9].

Causes

Potential causes for the decline include program trading, overvaluation, illiquidity, and market psychology.

The most popular explanation for the 1987 crash was selling by program traders.[10] U.S. Congressman Edward J. Markey, who had been warning about the possibility of a crash, stated that "Program trading was the principal cause."[11] In program trading, computers perform rapid stock executions based on external inputs, such as the price of related securities. Common strategies implemented by program trading involve an attempt to engage in arbitrage and portfolio insurance strategies. The trader Paul Tudor Jones predicted and profited from the crash, attributing it to portfolio insurance derivatives which were "an accident waiting to happen" and that the "crash was something that was imminently forecastable". Once the market started going down, the writers of the derivatives were "forced to sell on every down-tick" so the "selling would actually cascade instead of dry up".[12]

As computer technology became more available, the use of program trading grew dramatically within Wall Street firms. After the crash, many blamed program trading strategies for blindly selling stocks as markets fell, exacerbating the decline. Some economists theorized the speculative boom leading up to October was caused by program trading, while others argued that the crash was a return to normalcy. Either way, program trading ended up taking the majority of the blame in the public eye for the 1987 stock market crash.

New York University's Richard Sylla divides the causes into macroeconomic and internal reasons. Macroeconomic causes included international disputes about foreign exchange and interest rates, and fears about inflation.

The internal reasons included innovations with index futures and portfolio insurance. I've seen accounts that maybe roughly half the trading on that day was a small number of institutions with portfolio insurance. Big guys were dumping their stock. Also, the futures market in Chicago was even lower than the stock market, and people tried to arbitrage that. The proper strategy was to buy futures in Chicago and sell in the New York cash market. It made it hard -- the portfolio insurance people were also trying to sell their stock at the same time.[13]

Economist Richard Roll believes the international nature of the stock market decline contradicts the argument that program trading was to blame. Program trading strategies were used primarily in the United States, Roll writes. Markets where program trading was not prevalent, such as Australia and Hong Kong, would not have declined as well, if program trading was the cause. These markets might have been reacting to excessive program trading in the United States, but Roll indicates otherwise. The crash began on October 19 in Hong Kong, spread west to Europe, and hit the United States only after Hong Kong and other markets had already declined by a significant margin.

Another common theory states that the crash was a result of a dispute in monetary policy between the G7 industrialized nations, in which the United States, wanting to prop up the dollar and restrict inflation, tightened policy faster than the Europeans. U.S. pressure on Germany to change its monetary policy was one of the factors that unnerved investors in the run-up to the crash.[14] The crash, in this view, was caused when the dollar-backed Hong Kong stock exchange collapsed, and this caused a crisis in confidence.

Some technical analysts claim that the cause was the collapse of the US and European bond markets, which caused interest-sensitive stock groups like savings & loans and money center banks to plunge as well. This is a well documented inter-market relationship: turns in bond markets affect interest-rate-sensitive stocks, which in turn lead the general stock market turns.

See also

- Wall Street Crash of 1929 (Black Tuesday)

- List of largest daily changes in the Dow Jones Industrial Average

- Stock disasters in Hong Kong

References

- ↑ Browning, E.S. (2007-10-15). "Exorcising Ghosts of Octobers Past". The Wall Street Journal (Dow Jones & Company): pp. C1–C2. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB119239926667758592.html?mod=mkts_main_news_hs_h. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- ↑ Share Price Index, 1987-1998, Commercial Framework: Stock exchange, New Zealand Official Yearbook 2000. Statistics New Zealand, Wellington. Accessed 2007-12-12.

- ↑ "Dow Jones biggest percentage declines". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. 2008-09-30. http://www.sun-sentinel.com/business/sfl-flzdowbox0930sbsep30,0,7864544.story.

- ↑ "Financial Crisis: Dow Drops 504" (PDF). Seattle Post Intelligencer. 2008-09-16. http://seattlepi.nwsource.com/frontpage/SPI-20080916-A-001.pdf.

- ↑ "Setting the Record Straight on the Dow Drop". New York Times. 1987-10-26. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B0DE0D71F3EF935A15753C1A961948260.

- ↑ "The Day Stocks Rose but the Dow Plunged". WSJ.com Blogs: The Numbers Guy. 2008-10-01. http://blogs.wsj.com/numbersguy/the-day-stocks-rose-but-the-dow-plunged-423/.

- ↑ "Group of 7, Meet the Group of 33". The New York Times. 1987-12-26. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B0DEED8133AF935A15751C1A961948260.

- ↑ "Motley Fool's Black Monday 10th Anniversary 1987 Timeline". 1997-10-19. http://aol.fool.com/Features/1997/sp971017CrashAnniversary1987Timeline.htm. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- ↑ "Video: Tony Blair warns of the financial crisis". Monevator. http://monevator.com/2010/03/01/video-tony-blair-financial-crisis/. Retrieved 2010-03-01.

- ↑ The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, "Program Trading," by Dean Furbush accessed May 22, 2007

- ↑ Albert, Bozzo (10-12-2007). "Players replay the crash". Remembering the Crash of 87. CNBC. http://www.cnbc.com/id/21136884. Retrieved 2007-10-13.

- ↑ Paul Tudor Jones II Interview

- ↑ Annelena, Lobb (2007-10-15). "Looking Back at Black Monday:A Discussion With Richard Sylla". The Wall Street Journal Online. Dow Jones & Company. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB119212671947456234.html?mod=US-Stocks. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- ↑ Analysis: G20 doesn't even try to put brave face on debt mess Reuters, accessed June 6, 2010

Further reading

- "Brady Report" Presidential Task Force on Market Mechanisms (1988): Report of the Presidential Task Force on Market Mechanisms. Nicholas F. Brady (Chairman), U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Carlson, Mark (2007) "A Brief History of the 1987 Stock Market Crash with a Discussion of the Federal Reserve Response," Divisions of Research & Statistics and Monetary Affairs Federal Reserve Board, Washington, D.C.

- Securities and Exchange Commission (1988): The October 1987 Market Break. Washington: U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

- Shiller, R. (1989). Investor Behavior in the October 1987 Stock Market Crash: Survey Evidence. Boston: MIT Press. http://ideas.repec.org/p/nbr/nberwo/2446.html. in Shiller, Robert J. (1990). Market Volatility. MIT Press. ISBN 0 262 19290 X.

- Robert Sobel Panic on Wall Street: A Classic History of America's Financial Disasters-With a New Exploration of the Crash of 1987 (E P Dutton; Reprint edition, May 1988) ISBN 0-525-48404-3.

External links

- CBC Reports on Black Monday

- CNBC Remembering the Crash of 1987

- Guardian Black Monday photographs

- Motley Fool's Black Monday 10th Anniversary 1987 Timeline

|

|||||

|

|||||